Subterranean City

Once Shunned, Seattle’s Underground Today Welcomes Tourists

By Bill Hudgins

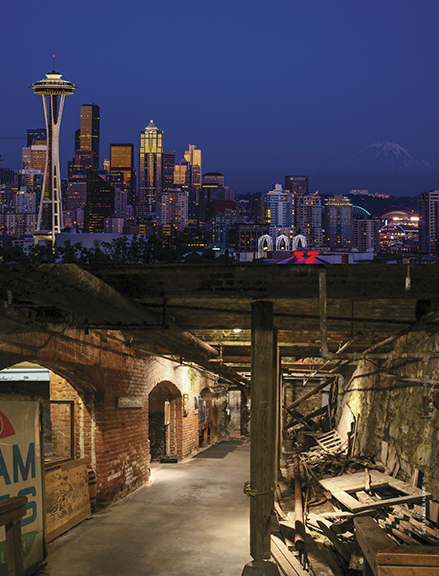

Say “Seattle,” and most people envision the Space Needle, which was built for the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair and soars 605 feet above the city. However, few people outside of Seattle know about another landmark that lies beneath the Pioneer Square historic district.

another landmark that lies beneath the Pioneer Square historic district.

Dating to the late 19th century, the Seattle Underground was the unintended result of a devastating fire and the tenacious city’s determination to rebuild. Once almost forgotten, its checkered past now makes it a popular tourist attraction.

Seattle’s first white settlers sailed into Elliott Bay in November 1851. They established a foothold at Alki Point, situated on what for centuries had been the traditional territory of the Suquamish and Duwamish Tribes.

The settlers soon relocated across the bay, founding a village at the heart of today’s Pioneer Square historic district. The location’s deep-water harbor was ideal for shipping timber cut from the thick surrounding forests. They named it Seattle in honor of Sealth, the Duwamish Indian leader, according to www.Seattle.gov.

Originally, Seattle was a mix of tidal flats fronting steep hills, and much of its early town was built on low-lying land conveniently near the harbor. Persistent flooding at high tide was a chronic problem.

Nevertheless, the high demand for lumber fueled Seattle’s growth. The city boomed in the 1880s after becoming a stop on the Northern Pacific Railway. Then, on June 6, 1889, the boisterous, self-confident city faced its greatest challenge when fire engulfed the downtown.

‘The Great Fire’

Conditions were almost perfect for “The Great Fire.” Except for a few brick buildings, most structures were built of wood. Even the water mains and sewers were made from hollowed-out logs. The spring weather had been unusually mild and dry, and the wind picked up during the afternoon. Compounding matters, the chief of the volunteer fire department was out of town, and the volunteers lacked training—and water, as they soon learned.

The fire started in the afternoon at a cabinetmaker’s shop near the intersection of today’s First Avenue and Madison Avenue. An assistant, John Back, was heating a pot of glue that boiled over and caught fire. Back threw water on the flames, but that only splashed the flaming glue onto the wood chips and turpentine on the floor. Workers fled the building.

The fire had spread to other buildings by the time the fire department arrived 30 minutes later. The alcohol in a nearby liquor store and two saloons exploded as they burned, and the fire leaped to other blocks.

The frantic firefighters tried to suppress the flames, but water pressure was low and dropped further as they fought the blaze. They tried running hoses down to Elliott Bay, but the lines were too short. Attempts to create a firebreak by dynamiting buildings also failed. The heat was so fierce that even the wooden water and sewer lines caught fire.

By the time the fire died down around 3 a.m. the next day, it had destroyed some 25 city blocks, including most of the business district, wharves, mills and railroad terminal. Though no deaths were reported, thousands of residents were left homeless, and an estimated 5,000 lost their jobs. On a positive note, the inferno killed an estimated 1 million rats.

The British poet Rudyard Kipling was touring Puget Sound at the time and landed in Seattle after the blaze. He described the scene as “a horrible black smudge, as though a Hand had come down and rubbed the place smooth. I know now what being wiped out means.”

Out of the Ashes

Confronted with enormous losses, Seattle immediately began to recover. Approximately 600 business owners met the next day to coordinate relief and commence rebuilding. The armory transformed into a makeshift dining hall to feed those who had lost their homes. Businesses and restaurants reopened under tents. The city declared martial law for two weeks and swore in some 200 temporary deputies to prevent looting. It then banned wooden buildings and decreed new construction should be brick and stone. Rebuilding started quickly, and within a year, some 465 new structures had risen phoenix-like from the ashes.

Meanwhile, the fire presented an opportunity to solve the area’s flooding and drainage problems. After much discussion, city leaders proposed regrading downtown by raising the street level as much as 22 feet in certain places to block the surging tides. The city also assumed control of the water system, replacing the charred wooden pipes and laying new sewer lines for proper drainage.

To execute this plan, the city erected retaining walls around each block on either side of the old streets. Water cannons were then used to flatten a nearby hill and sluice the mud between the retaining walls. Once the water drained away, the city built new streets and sidewalks on top, said Terrilyn Johnson, co-owner of Beneath the Streets tour company.

The project succeeded in raising and leveling the streets, but it also meant the storefronts were now underground, connected by hollow tunnels between the retaining walls and the buildings. Businesses remained open throughout construction, and customers had to use ladders to get down to the subterranean storefronts and traverse between blocks. The city installed glass skylights to provide illumination.

As the project proceeded, building owners constructed new storefronts on what had been their second and, in some cases, third floors. Most of the regrading was complete by the mid-1890s, Johnson said.

In 1897, the Klondike Gold Rush drew an estimated 100,000 people to Seattle to board Alaska-bound ships. The city boomed as merchants sold overpriced equipment to the would-be miners. Pioneer Square and the Underground bustled with saloons, brothels and other shady establishments.

After the gold rush, Pioneer Square began to decline. Reputable business owners vacated the increasingly seedy neighborhood, and more disreputable establishments arrived, taking advantage of low rents and lax policing, according to the tongue-in-cheek history on the Bill Speidel’s Underground Sidewalk skylights Tour website.

The rats soon resurged, prompting the city to briefly close the Underground and declare a bounty on rodents after three people died from bubonic plague. Although the area soon reopened, it continued to decline.

By the 1960s, the Underground was almost a shadowy myth for most Seattleites, and there was talk of razing much of the area for a highway. Fortunately, a preservation movement emerged, comprising artists, architects, historians and others who loved the old buildings and wanted to save the area.

comprising artists, architects, historians and others who loved the old buildings and wanted to save the area.

One of the leaders was Bill Speidel, a newspaperman, public relations executive, historian, author, preservationist and bona fide Seattle character. In 1963, The Seattle Times published a guest column detailing Speidel’s explorations of the Underground and announcing when he planned to go again. Some 500 people showed up and “donated” $1 each for the tour. He soon founded Bill Speidel’s Underground Tours.

In 1970, Pioneer Square became both a National Historic District and a local preservation district. The 88-acre district includes one of America’s largest collections of Richardsonian Romanesque buildings, and some of their former storefronts are part of the Underground tours.

Visitors can expect to see the retaining walls, supporting arches, original first story exteriors, and, rarely, relics. Vandals and souvenir seekers plundered the Underground for years, carrying away signage, decorative elements and miscellaneous objects. The tunnels are now locked when not in use, Johnson said.

Some of the storefronts are open while others are closed off. Old and new pieces of infrastructure—pipes, conduits and cables—run through the tunnels. Some spots are so full of utility-related structures that they are nearly impassable, Johnson said.

Some of the sidewalk skylights remain, with their prisms turned purple from the effect of sunlight on manganese in the glass. Like those late 19th-century Seattleites, Underground visitors must ascend and descend stairs to cross streets.

Tour companies like Speidel’s and Beneath the Streets pay rent to the building owners for access, Johnson said. The tunnels are well-lit, there are wooden walkways to minimize dust and damage, and the city conducts regular safety inspections. For more information, visit Beneath the Streets at www.beneath-the-streets.com or Speidel’s www.undergroundtour.com.